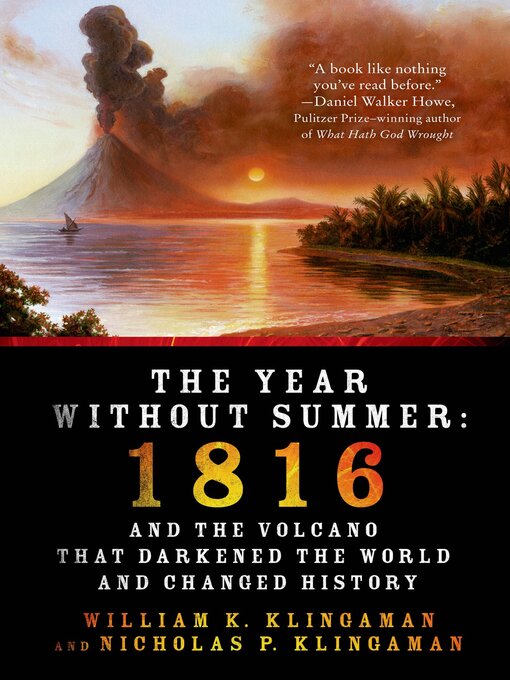

Like Winchester's Krakatoa, The Year Without Summer reveals a year of dramatic global change long forgotten by history

In the tradition of Krakatoa, The World Without Us, and Guns, Germs and Steel comes a sweeping history of the year that became known as 18-hundred-and-froze-to-death. 1816 was a remarkable year—mostly for the fact that there was no summer. As a result of a volcanic eruption in Indonesia, weather patterns were disrupted worldwide for months, allowing for excessive rain, frost, and snowfall through much of the Northeastern U.S. and Europe in the summer of 1816.

In the U.S., the extraordinary weather produced food shortages, religious revivals, and extensive migration from New England to the Midwest. In Europe, the cold and wet summer led to famine, food riots, the transformation of stable communities into wandering beggars, and one of the worst typhus epidemics in history. 1816 was the year Frankenstein was written. It was also the year Turner painted his fiery sunsets. All of these things are linked to global climate change—something we are quite aware of now, but that was utterly mysterious to people in the nineteenth century, who concocted all sorts of reasons for such an ungenial season.

Making use of a wealth of source material and employing a compelling narrative approach featuring peasants and royalty, politicians, writers, and scientists, The Year Without Summer by William K. Klingaman and Nicholas P. Klingaman examines not only the climate change engendered by this event, but also its effects on politics, the economy, the arts, and social structures.

- Available now

- New eBook additions

- New kids and teen additions

- Most popular

- Professional Development for Librarians

- O Captain! My Captain!

- See all ebooks collections

- Available now

- New audiobook additions

- New kids and teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- See all audiobooks collections

- Popular Magazines

- Just Added

- Cooking & Food

- Home & Garden

- Fashion

- Health & Fitness

- Celebrity

- News & Politics

- Business & Finance

- Hobbies & Crafts

- Travel & Outdoor

- Popular Magazines

- See all magazines collections